ΕCONOMIST - May 26th 2012

The level of further integration necessary to deal with the euro crisis will be hard to square with the increasing cantankerousness of Europe’s voters

For the past six decades, steps forward to greater European union have taken place at moments of incipient crisis. None, though, has been taken in a time of disaster. The next leap in integration looks set to change that.

All the plausible solutions to the self-inflicted mess of the euro crisis require a significant new level of fiscal and potentially political union, not least because some countries, such as Germany, actively want greater political union and see it as the price of their co-operation. In order to make any such solution work, Europe's elites will have to address a problem they have long shirked: that of the democratic deficit at the heart of integration. And they will have to do so under the worst of conditions.

The past week's near-continuous high-level summitry has done little to reduce the risk of a Greek exit from the euro, which rose to higher levels than ever after the inconclusive results of the country's election on May 6th. The risk shows no signs of receding before the next vote, on June 17th. After that, risk may become reality (see article).

A consensus is slowly emerging that, whether a Greek exit is to be averted or weathered, there will have to be a greater level of integration in the euro zone, with tighter constraints on the freedom of national governments. Some countries, under some conditions, may put up with seeing their governments so constrained for a while: Italy and Greece (until recently) have had unelected, technocratic prime ministers, in large part as a result of pressure from outside creditors. But elsewhere, and in the long run, people seem likely to want to do the constraining they think proper by means of the ballot box, rather than having it forced upon them.

If only you'd asked

A new paper written for the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) by Ulrike Guérot and Thomas Klau quotes a German government official putting his finger on the nub of the problem: “the weakness of the system is not about spending and how to promote growth, but about legitimacy.” A move to fix the euro crisis with greater political union that does not take this into account will, at best, store up grave political problems for the future. At worst it will prove impossible to implement at all because of the politics of the here and now.

The architects of the 1992 Maastricht treaty, who included Jacques Delors, then European Commission president, and Helmut Kohl, then German chancellor, always wanted political union to accompany the monetary union that the treaty envisaged. Some critics of the project, including the German Bundesbank, argued that the single currency would not work without it.

But Maastricht, like many edifices, did not end up quite as the architects had wanted. There were rules on budget deficits that implicitly reached into the political decision-making of the member states. But they were not taken seriously, and swiftly broken without censure.

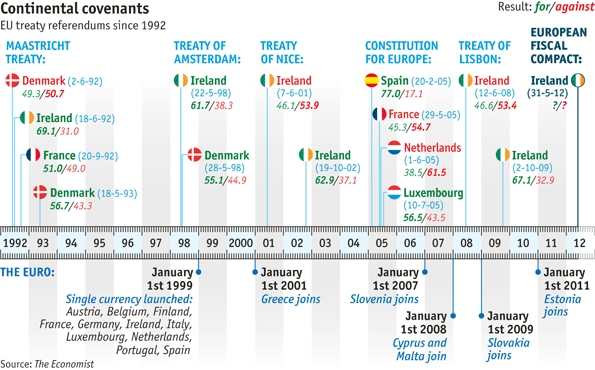

In what has become something of a pattern in Europe, most voters were not asked whether they wanted such a treaty. Those who were showed themselves equivocal: a French referendum on the Maastricht treaty squeaked through by the narrowest of margins. Most of the euro zone's citizens came to accept the currency, as they have accepted the European Union (EU), because until the crisis hit it seemed to bring clear benefits, or at least to do no harm. Once things started to go wrong, though, the voters protested.

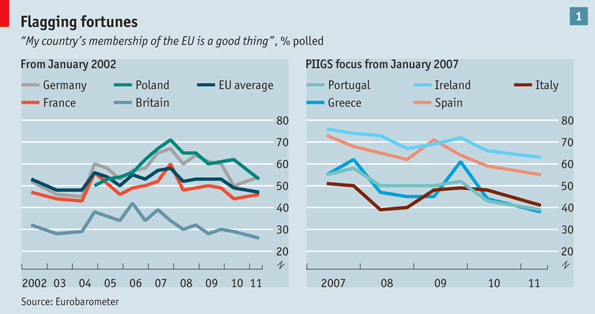

Since the euro crisis began in early 2010, no fewer than nine of the zone's 17 national leaders have been ejected from office. The approval ratings for many countries' membership of the EU have been declining (see chart 1). Voters have been giving more support to fringe parties. The Greek election took this swing to extremes, with almost 70% of the votes going to parties that wanted to modify or tear up the country's bail-out deal. But something similar, if more muted, is visible from Finland to the Netherlands to Germany. It can be hard to tell anti-incumbency feeling from anti-Brussels feeling—but that is part of the problem. With no way to influence Brussels except through governments that seem not to be listening, the cynical antipolitics of impotence easily takes hold.

Democracy, eurocracy

This democratic deficit in Europe's institutions is hardly new. Europe's first helmsmen deliberately eschewed populism—the tool of fascists and communists, in their eyes—in favour of dispassionate well-planned gradualism as a road to the sort of ever closer union that would banish war from the continent. Thanks to the decisive intervention of Charles de Gaulle—whose “empty chair policy” meant refusing to send French emissaries to Brussels, and thus paralysing the nascent institutions until his demands were met—the project soon veered from a more centralised vision to a more inter-governmental one; but the powerful non-national institutions remained.

Although it was an elite venture light on such fripperies as voters' consent, still less accountability, the European project incorporated many less direct democratic features from the start. Most fundamentally, membership was only open to democracies. The inter-governmental Council of Ministers and European Council—now the EU's prime driver of policy—thus represented the people. The commission—its members chosen by elected national governments—would propose legislation; it would then have to be approved by both the Council and the European Parliament, another mode of legitimation. To begin with the parliament's members, too, were nominated by governments from their national parliaments. From 1979 onwards the members have been elected directly.

The role of governments in setting policy and appointing personnel was one response to concerns about democratic accountability within the nascent EU. Another was to argue that what really mattered for European citizens was “output legitimacy”: the notion that, so long as the common project produced evident benefits in the form of prosperity, economic opportunities and job creation, voters would accept it, and even come round to welcoming it.

A third was to claim that the European project was mainly about technical matters such as competition, regulation and rules for the single market, all of which could happily and unproblematically be dealt with out of sight of the voters (in most countries they are dealt with technocratically). The argument was that, so long as the EU did not touch the most important political issues for ordinary voters—such as tax, spending, education, defence or health care—its apparent lack of accountability would not matter.

Coming unstuck

Now the crisis has struck, all the putative responses to the democratic deficit are being found wanting. The qualified majority voting introduced by the Single European Act of the 1980s and the subsequent enlargement of the union mean that nations, especially small ones, can frequently feel marginalised, and their electorates voiceless; the system is opaque, complex and remote. Countries outside the euro zone are not party to some decisions, which can make them fear marginalisation; the “six pack” of fiscal regulations agreed last year and the newly devised fiscal compact erode even further the ability of a government within the zone to control its own fate. Crucially, the pact imposes fines on governments in breach of its strictures automatically, unless a qualified majority of all the others votes against doing so. In 2002 Francis Mer, newly installed as French finance minister, dismissed commission requests for budget cuts to comply with the stability and growth pact by saying that “France has other priorities.” Pierre Moscovici, François Hollande's new finance minister, stands no chance of being similarly highhanded. This lack of governmental override worries not just debtor nations but also some creditor countries such as the Netherlands—and even German states.

The other responses to the democratic deficit look even more tattered. Output legitimacy is a hard sell when the outputs voters use to reach a judgment are a crisis they didn't create and austerity they don't want. The idea that the EU is all about distant technical adjustments is laughable now that the euro is impinging on many basic functions of sovereign national governments, most obviously in Greece, Ireland and Portugal, but also in all the parties to the fiscal compact. If the euro is to survive, it will likely do so by impinging on them yet further.

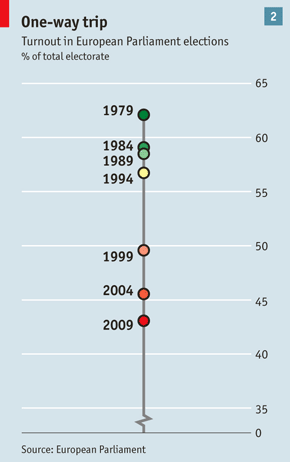

And what of the European Parliament? It has, if anything, widened the deficit it is meant to make up. It has increased its powers with every EU treaty, including the fiscal compact; but it has seen no parallel growth in its legitimacy. In the commission and in national capitals alike, frustration with the parliament has been growing. It is almost always in favour of new regulation and always in favour of more spending. Any claim that this is what the voters want is undermined by the fact that the voters show ever less interest in it. At every election for the European Parliament since 1979, the turnout across the continent has plumbed a new low (see chart 2). National elections see higher turnouts almost everywhere. And if fringe parties are doing well in many regional and national elections—as the Pirate Party has been in Germany, and Beppe Grillo's “Five Star movement” in Italy (seearticle)—they tend to do even better in votes for Strasbourg.

How to elect a president

If a more tightly knit euro zone needs better democratic credentials, then there is no shortage of ideas about what to do. The most obvious is to limit the extent of centralised powers. Constraints on national budget deficits—which the fiscal compact wants written into national constitutions—do not need to mean common rules on spending or harmonisation of taxes. The long-established principle of subsidiarity should leave as much discretion as possible to national or local levels of government. Yet much tighter constraints on fiscal policy will still curtail national freedom, so they may need to be offset by schemes designed to increase democratic legitimacy.

Old-style federalists say this means now is the time to bolster the European Parliament still more. One possibility would be to up the ante in its elections by making them indirect elections for the commission president as well. The idea is that the big political groups (the centre-right European People's Party, the Socialists and the Liberals) should each have preferred candidates, and the member states should agree to choose the candidate of the block that does best at the next elections, due in 2014.

Such schemes ignore the degree to which the parliament has become part of the problem, rather than the solution—unloved by the EU's institutions, the governments of its member states, and its citizenry. In its judgment on the Lisbon treaty, the German constitutional court cast doubt on the democratic credentials of the European Parliament, arguing that the Bundestag had greater legitimacy.

Another possibility, if elections are the answer, is to avoid the parliament and elect the president of the commission directly. Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany's finance minister, has espoused this idea, most recently in his acceptance speech for the Charlemagne prize on May 17th. Last November, his party, the Christian Democratic Union that Angela Merkel leads, also came out in favour of an elected president. The opposition German Social Democrats are also interested.

As in many matters, German enthusiasm is not enough in itself to win the day. Direct elections for a president (unlike appointment on the advice of the parliament) would require a new treaty. Even before the euro crisis, new treaties had proved hard sells (see timeline). The EU's Lisbon treaty crept into force only because 26 of the 27 member states avoided putting it to a vote, and the 27th, Ireland, allowed itself a second vote after the first went the wrong way.

The executive and the excluded

If treaties are to be changed, though, Vernon Bogdanor, a professor at King's College, London, would push the elections yet further, and elect the entire commission on a Europe-wide basis. He argues that the euro zone is at a similar stage to the embryonic United States in the early 1780s. That was the moment when Alexander Hamilton took the big step of federalising the states' debts. In the euro zone, too, Mr Bogdanor suggests, it is time to move towards federalism with a new democratic input: hence the notion of an elected European Commission. To those who claim that there is no European demos to underpin such democracy, he argues that a Europe-wide election will itself create one.

This is the sort of thing that Larry Siedentop, a former Oxford academic, warns against under the heading of “faux democracy”. Sharing the general dissatisfaction with the European Parliament, Mr Siedentop doubts things can be improved by another elected body. In his prescient “Democracy in Europe”, published in 2000, Mr Siedentop warned that, after creating the single currency, “European elites today are in danger of creating a profound moral and institutional crisis in Europe—a crisis of democracy.” His suggested solution was to set up an appointed Senate, chosen from national parliaments; to those who feel democracy needs elections he points out that America's Senate was appointed until 1913.

An alternative, and attractive, source of democratic accountability might be found in Europe's national parliaments. Before 1979 there was an umbilical link between the European Parliament in Strasbourg and national parliaments, with some members circulating between the two. Now the different parliaments tend to see each other as rivals rather than as colleagues trying to hold the executive to account. The Lisbon treaty gives national parliaments only a limited role. Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform in London, suggests enlarging this. He would give more prominence to COSAC, the group that brings together national parliaments' European affairs committees, perhaps putting a delegation of national MPs in Brussels to work more closely with the European Parliament. Others want to give the budget committees in national parliaments a clear role in monitoring and applying the fiscal compact.

A continuing issue in all this is the balance between an inter-governmental and a federal system. Those leaning towards a bigger role for national parliaments and governments naturally favour the first. But Mr Klau of the ECFR points out that such a method makes it more likely that Germany, the biggest power and also largest creditor, will be identified as a target by the rest. Inter-governmentalism favours big countries, which is why small ones talk up the role of Brussels.

The case for greater national involvement in running the euro zone is very strong. Whether Greece leaves or stays, the euro zone must be more politically integrated or fall apart. But deeper political union could provoke a backlash, in both creditor and debtor countries, that brings the whole system crashing down. In last year's Finnish election the True Finns under Timo Soini went from almost no support to close to 20% by campaigning against euro-zone bail-outs. In the Netherlands Geert Wilders, who has just precipitated an election by withdrawing his support from the government, is now running as much on an anti-bail-out ticket as his more familiar anti-Muslim one. France's National Front has long been anti-euro as well as anti-immigrant, and Marine Le Pen's stand against the single currency contributed a lot to her strong showing in the first round of the presidential election.

Given that voters are making their antipathy heard by means of their national elections, they might feel better represented if national MPs and governments played a bigger role in policing the boundaries of political union of the euro zone. But this may be too sanguine. A significant number of voters clearly want not a more democratic version of the EU, but a fundamentally different institution. With views highly polarised, it is hard to see how any useful treaty could now get accepted by all 27 nations—which is one of the reasons why the fiscal compact has an opt-in system. When Ireland votes on the compact on May 31st, it will be voting in or out for Ireland alone, not threatening to block everyone else.

If Europe seeks a new political constitution, though, a dramatic lurch towards a rejectionist or extremist party on one country could lead to a break-up of the club. And there is also a profound structural problem. The new round of political integration is being driven by the need to govern the euro zone better; but ten of the 27 are not part of it. And although many of them have historically aspired to join, Britain and Denmark have formal opt-outs from the euro, and Sweden is also unlikely to join for many years, if ever. These countries have a strong interest in ensuring that, as the euro zone becomes more integrated, they do not lose their influence in debate or their part in decisions. But their voters are unlikely to accept commitment to a stronger political union. David Cameron's “veto” of the fiscal compact in December 2011 was seen as a petulant obstacle to progress by many of his fellow heads of government; his party's supporters in Britain greeted it with inordinate enthusiasm.

When the architects of Maastricht were unable to produce a political union some of them comforted themselves with the idea that a common currency would in and of itself bring further economic integration from which political integration would naturally flow. They did not foresee that it would do so by throwing the continent into crisis. And they did not provide the mechanisms by which the citizens of the union could feel they were both in part to blame for the problem, as some are, and in a place to help find a solution. A political settlement that protects the euro without incorporating new ways to get and earn their assent is unlikely to last long—or to deserve to.

Σχετικά με τον συντάκτη της ανάρτησης:

Η ιστοσελίδα μας δημιουργήθηκε το 2008.Δείτε τους συντελεστές και την ταυτότητα της προσπάθειας. Επικοινωνήστε μαζί μας εδώ .

9 Ιουνίου 2016 στις 2:55 π.μ.

Thank you for the info. In your opinion, is it better to disband the euro zone? Greetings from young entrepreneurs

Tangki Fiberglass

Jual Septic Tank